Rising temperatures and extreme weather events are becoming the world’s new normal. In June 2021, a record-breaking heat dome settled over Western Canada, causing 619 heat-related deaths in British Columbia. As extreme heatwaves become more frequent, cities must reassess their strategies to adapt to climate change and protect populations at greater risk.

One of the most powerful tools cities have to fight extreme heat? Street trees. They play a key role in reducing the urban heat island effect, a critical challenge amplified by traditional paving practices. However, street trees are often planted in constrained environments without adequate conditions to grow, resulting in damage to both the trees and the surrounding infrastructure.

So how can the City of Vancouver preserve and sustain its urban forest while keeping streets and sidewalks safe and functional?

A depaving approach to climate adaptation

To help answer this question, Sustainability Scholar Trey Schiefelbein conducted an analysis to identify streets in the City of Vancouver that require rehabilitation or replacement. His report offers recommendations for depaving opportunities, allowing these streets to take on new roles that address the climate crisis, reduce repair costs, and support the City’s Climate Emergency Action Plan targets.

“While there is no silver bullet to address the effects of climate change, depaving is one of many available tools to create more environmentally and socially just cities today and into the future.”— Trey Schiefelbein, UBC Sustainability Scholar

Using a multi-criteria GIS analysis, Schiefelbein mapped where paving, urban heat, tree canopy cover and equity intersect in our streets. To understand these relationships, the report drew from four key datasets:

- Pavement Condition Index (PCI): Assesses the state of street segments, from “failed” to “good,” based on cracks, potholes, and other damage.

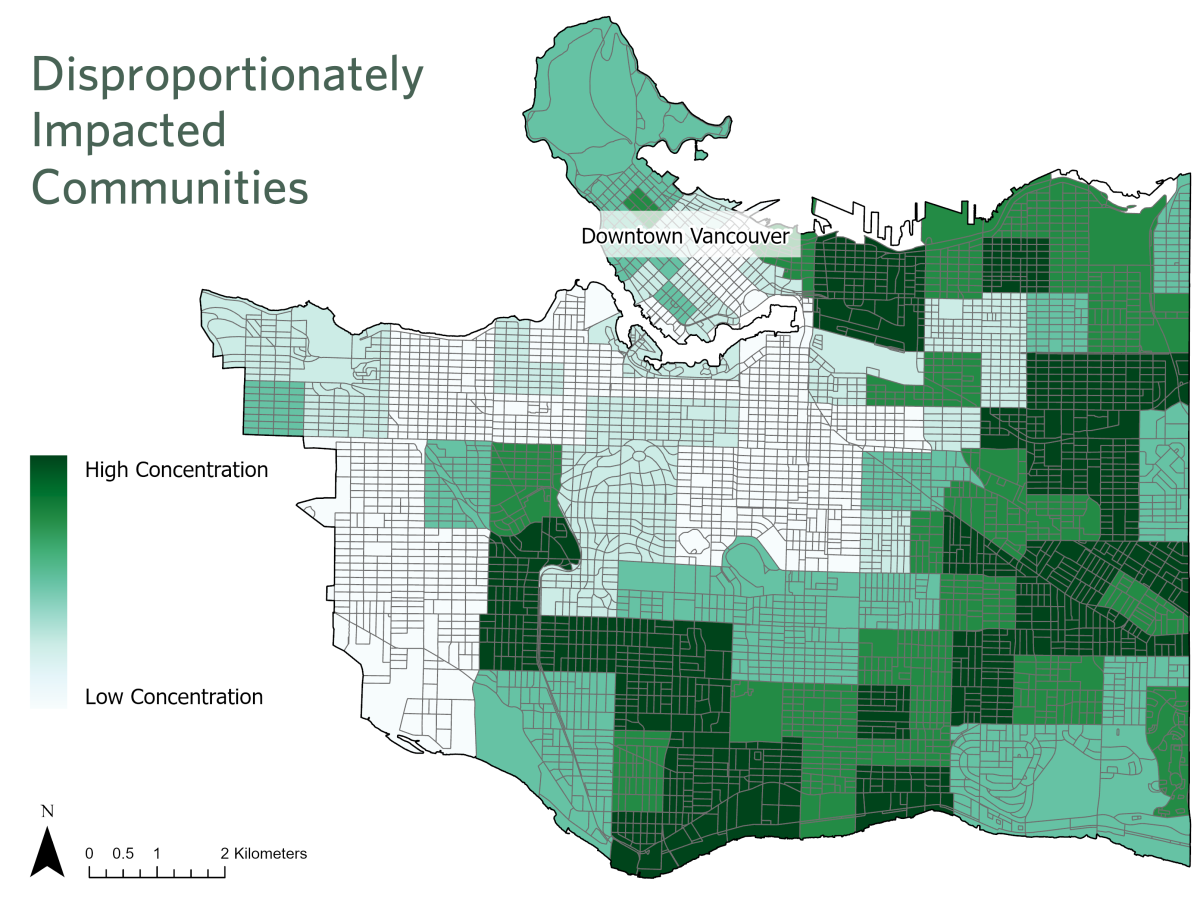

- Disproportionately Impacted Populations (DIP) index: Developed by the City’s Transportation Planning team, this index identifies areas where residents face systemic barriers based on demographic and socioeconomic factors.

- Urban Heath Watch: Captures surface temperatures from August 16, 2020, between 3–4 pm—one of the hottest days of the year— revealing clear disparities between Vancouver’s east and west sides.

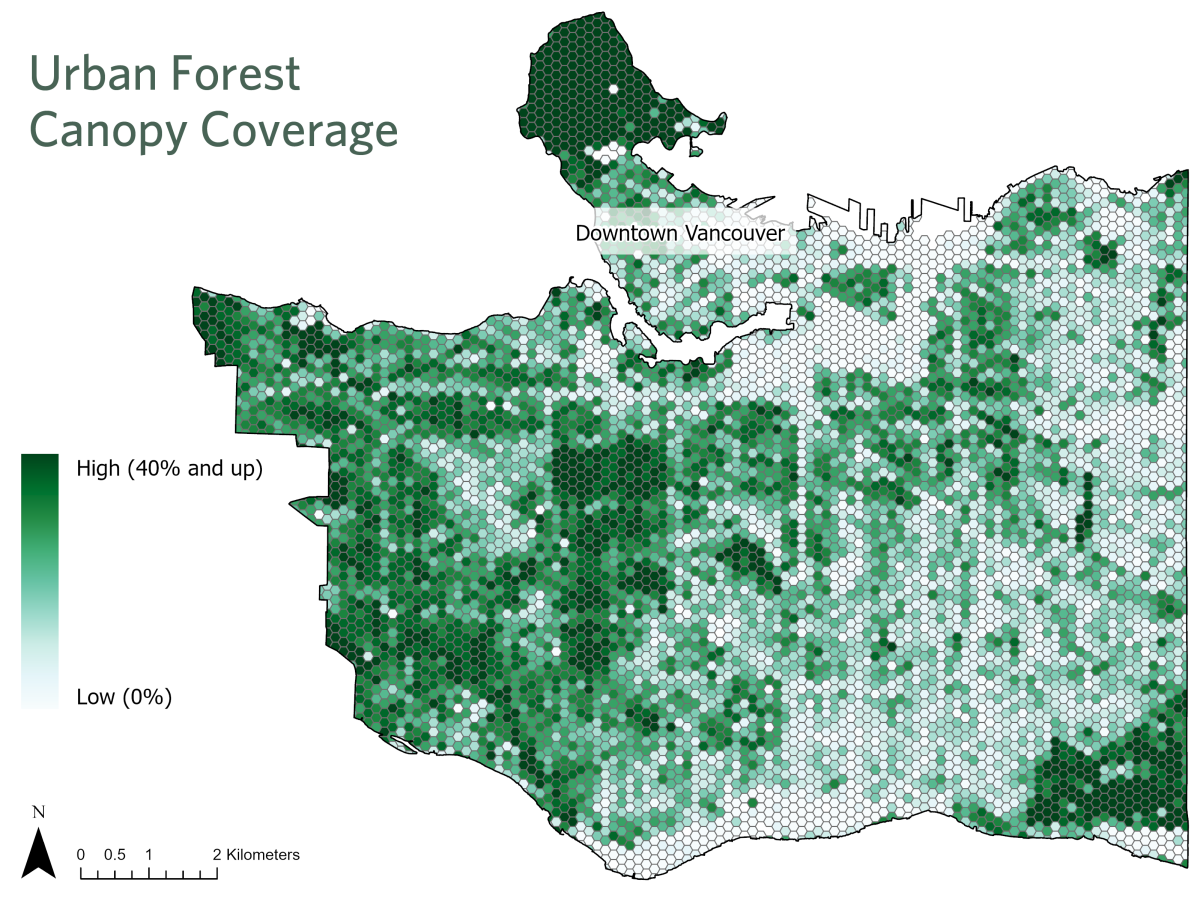

- Tree Canopy Cover: Indicates how much land is shaded by trees when viewed from above.

By layering these datasets, the analysis shows potential depavement street segments with poor pavement condition, in areas with a high DIP score, high surface temperatures, and low canopy cover.

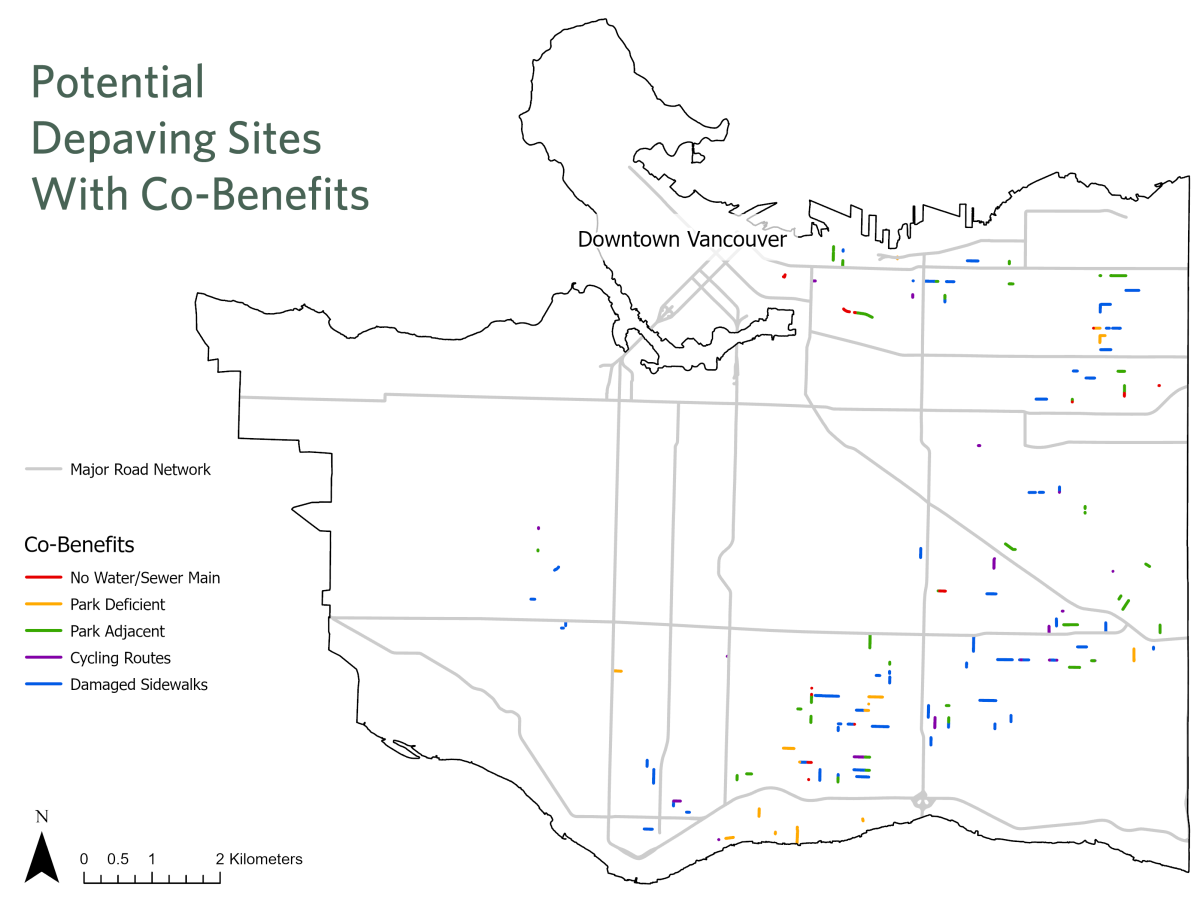

This was then compared to other co-benefits of depaving —specific circumstances that make a depaving project more practical. These include areas where sidewalks are in disrepair, proximity to parks, connections to bike routes, and locations without underground utilities. Streets where these features overlap are considered strong candidates for depaving.

Learning from other cities

The report also shares several case studies from cities like Montreal and Portland, where community-driven depaving efforts have restored natural systems in heavily paved areas. A key lesson learned: local organizations played a vital role in these projects. These groups collaborate with stakeholders to identify depaving opportunities, mobilize volunteers, promote education, build more resilient neighbourhoods, and advocate for policy changes that address environmental and social inequities.

Turning opportunities into action

Based on the GIS analysis and the evidence provided by case studies, Schiefelbein’s report provided a series of actionable recommendations to advance depaving practices and produce long-term results that support street trees and other ecological and social benefits:

1. Follow a quick and efficient approach: Not every depaving project needs to be large or complex. The City can pilot fast, low-cost interventions at smaller locations that involve simply removing sections of impervious surface to create space for green infrastructure. Precedents from around the world demonstrate that even small actions can yield significant results.

2. Act strategically: Implement a targeted approach that strategically selects specific areas for depaving —like individual parking stalls, partially reducing the width of streets, and reconfiguring sidewalks. This approach mirrors successful tree-planting strategies already underway in the Downtown Eastside and Marpole neighbourhoods.

3. Foster cross-team collaborations: Establishing clear communication across City departments will ensure that depaving efforts support multiple goals—from biodiversity to accessibility to traffic management and transportation design.

4. Create opportunities for community involvement: Community participation strengthens outcomes and builds more vibrant neighbourhoods. Residents can provide their feedback and help select depaving sites that can be maintained over time by volunteer gardeners and local associations.

5. Stay flexible: While community-led efforts are ideal, some tasks—like tree planting or utility maintenance— require City expertise. Addressing technical needs early allows the City to plan strategically, while supporting community-driven design and long-term success.

These recommendations are already influencing the City’s approach to roadway rehabilitation. Instead of defaulting to repaving, each project is now assessed to determine if partial or full depaving is possible—especially on low-traffic streets. The work has also enabled cross-departmental collaboration, integrating depaving into the City’s annual road rehab planning, balancing infrastructure needs with climate goals.

“Trey’s work didn’t just ask if we should depave—it showed how. Now, every time we review a road, we ask: Could this space serve our climate goals better as green infrastructure?”— Ross McFarland, Capital Program Manager, Engineering Services - Streets Design, City of Vancouver

A follow-up project to further support our urban forest

Schiefelbein’s work laid the foundation for future research. In a follow-up project, Sustainability Scholar Elliot Bellis explored how paved environments impact the health of street trees. Bellis’ report offers actionable recommendations to improve the City’s design standards—from tree pit retrofitting to sidewalk and boulevard design layouts—ensuring a better future for both trees and people.

The project ‘Rethinking Street Pavement Rehabilitation Practices to Support the Urban Forest’ was completed by Trey Schiefelbein, a 2022 participant in the Sustainability Scholars Program, managed by the UBC Sustainability Hub.

Learn more about the UBC Sustainability Scholars program.