Words by Nina Huh.

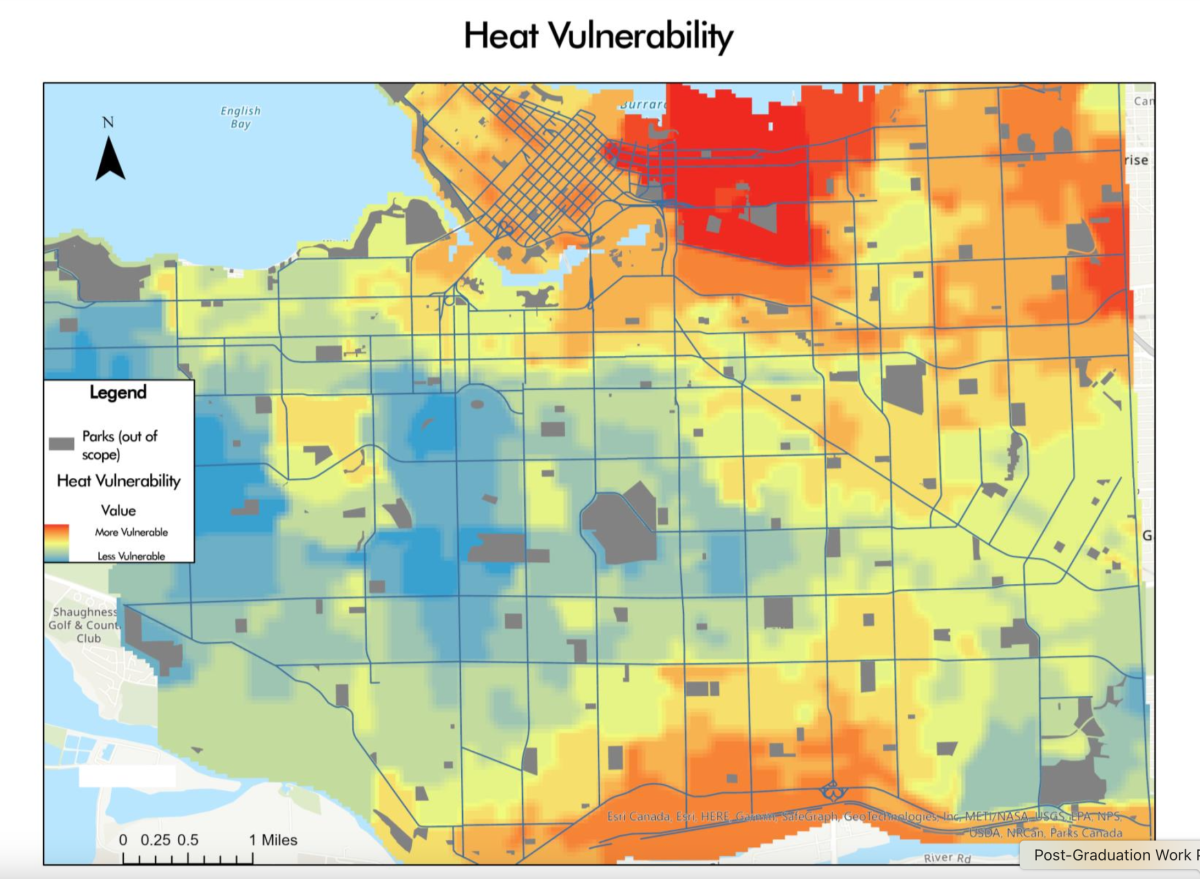

Access to drinking water is an essential human right. In 2021, British Columbia experienced a devastating heatwave that resulted in over 600 deaths (BC Gov News, 2021). With similar extreme heat events expected to increase in frequency and intensity as a result of human-induced climate change, maintaining and ensuring access to water for vulnerable populations is more important than ever before.

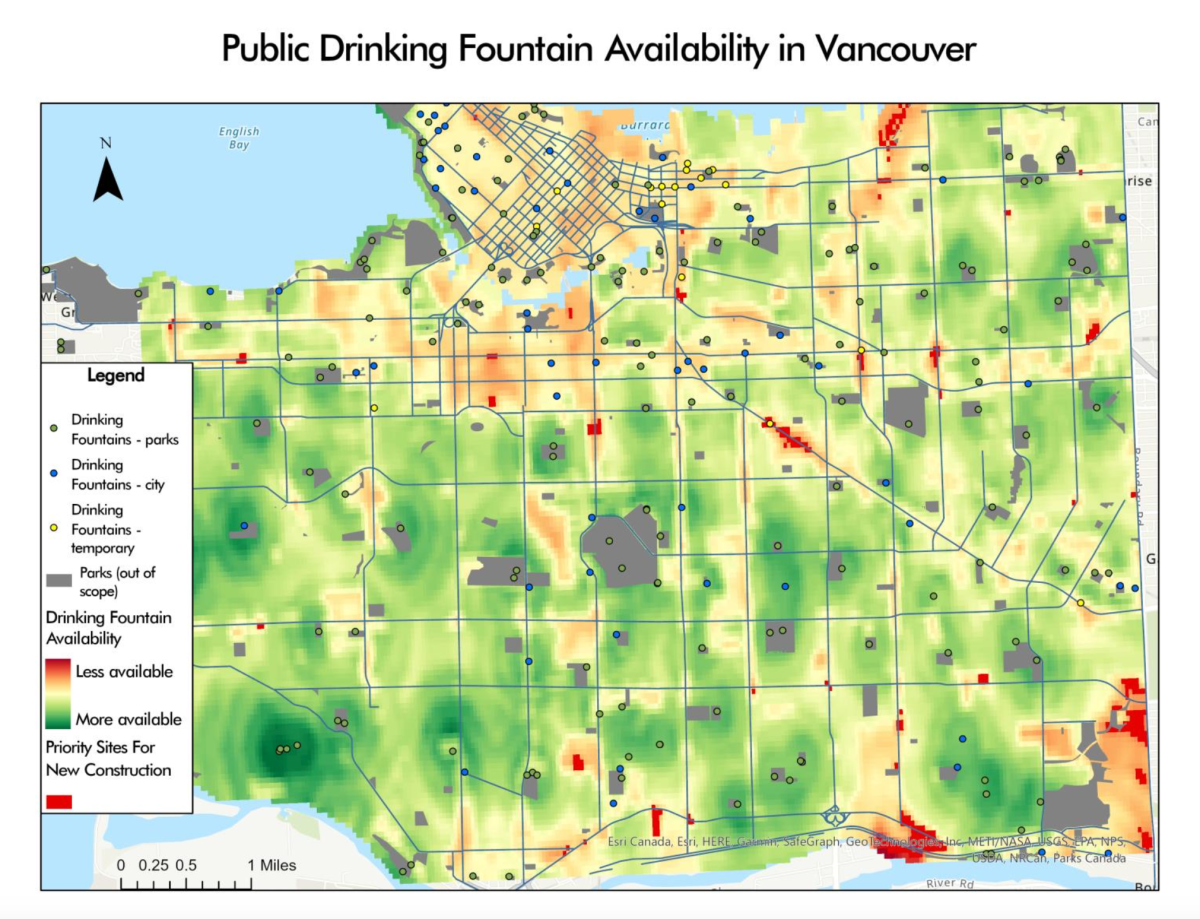

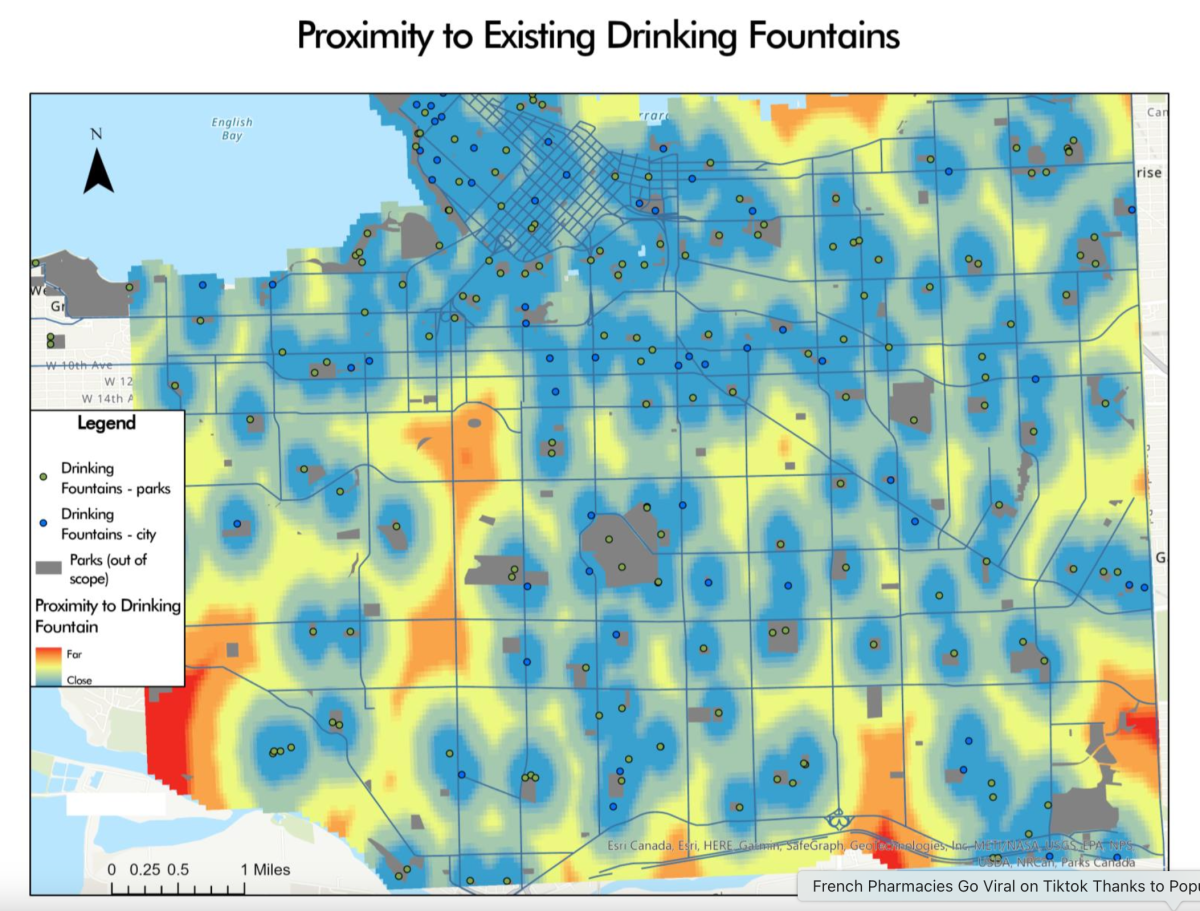

The City of Vancouver provides over 200 public drinking water fountains, but they are not always distributed widely or equitably enough. To address this issue, Sustainability Scholar Nick Gandolfo-Lucia used ArcGIS Pro to analyze spatial data to examine potential sites for new fountains to improve access to drinking water throughout the city. To identify potential sites, Gandolfo-Lucia accounted for the location of existing fountains, access to water mains, density, parks, and vulnerability to heat hazards.

Filling the gaps: targeting areas in need

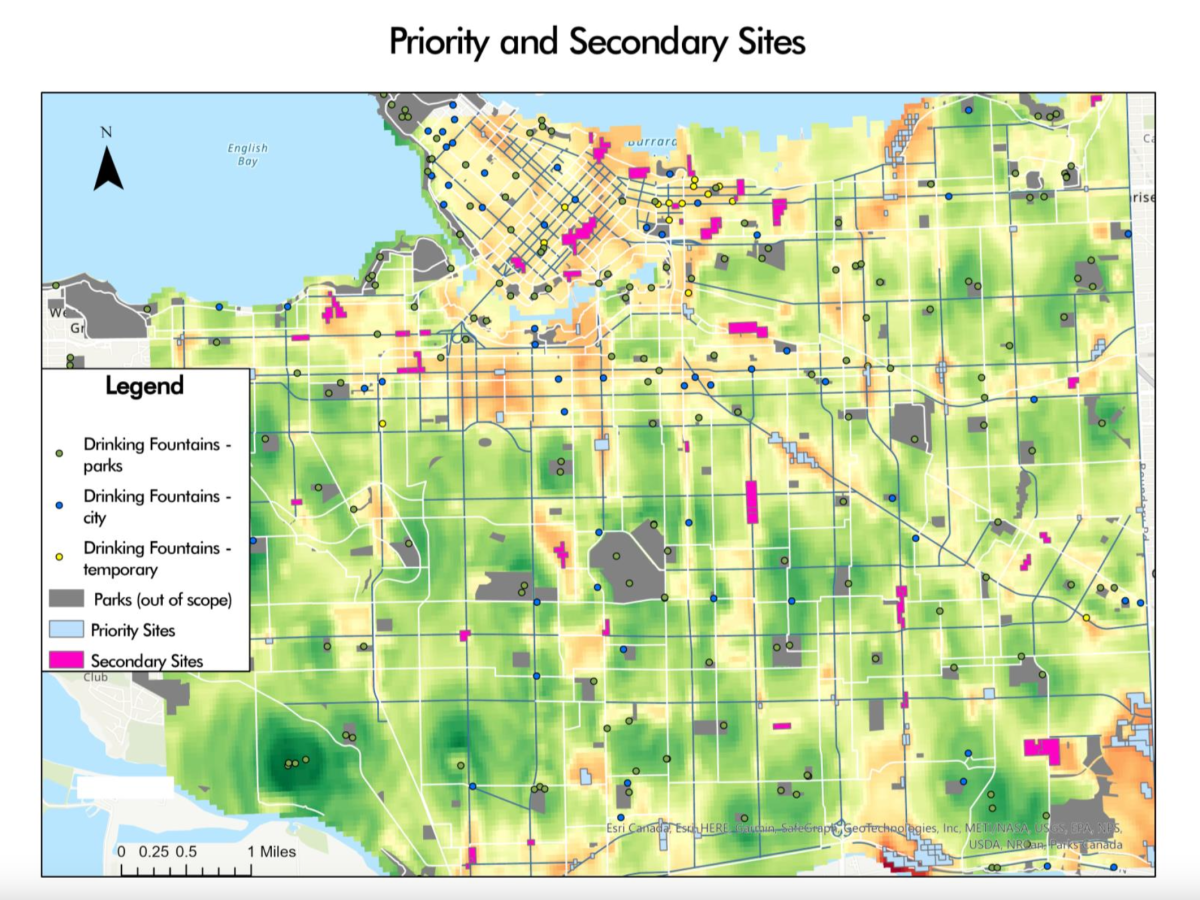

The report highlighted 29 priority and 18 secondary sites for water fountain construction over the next five years. The priority sites in particular will benefit areas with greater need: 60% of underserved areas will be upgraded to match the level of service throughout the rest of the city.

The report’s findings strongly support the installation of permanent fountains in areas facing significant social challenges, such as vandalism and homelessness. The fountains will provide access to clean water, which is a human right and essential in addressing extreme heat impacts, to communities that are the most vulnerable and underserved. "The report identified areas we thought were lower priority but turned out to be higher need … this shifted our focus and resource allocation,” noted Robyn King, Program Coordinator for the Access to Water at the City of Vancouver. "The report is now a foundational piece…it’s integrated into our asset management plans, business cases, and future projects.”

60% of underserved areas will be upgraded to match the level of service throughout the rest of the city.

Gandolfo-Lucia notes that consultation with community groups is key – even if the municipal government or a map shows the need for a fountain at a certain location, community groups have valuable insights that may differ. The report emphasizes a stronger need to advocate for drinking fountains in the Downtown Eastside. While using water fountains is more of a matter of education and personal choice for those with secure housing, for individuals without stable housing or reliable access to water, it is a crucial necessity.

Community members who took part in informal interviews also pointed out that community groups have distributed reusable bottles during heatwaves in the past; such initiatives, in combination with the construction of new fountains, would take the burden off of community groups to provide water during extreme heat events. So aside from ensuring access to drinking water year-round, increasing the availability of drinking fountains throughout the city will also help reduce single-use plastics.

A five-year plan for Vancouver’s drinking water fountains

Gandolfo-Lucia created a five-year plan to deliver the construction and installation of these water fountains: the first steps entailed visiting the proposed sites and ensuring they were fit for construction, and liaising with community groups.

After construction is complete, Gandolfo-Lucia recommended developing a more objective index for what constitutes an adequate level of public drinking water access in the city. Collaboration with the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation is also a possibility, so that the city and parks board can coordinate their facilities.

A city-led reusable water bottle distribution and education program is another possibility voiced by community members. While this report focused on permanent fountains as a part of a five-year plan, participants also noted the importance of temporary fountains for short-term use during hot summers to address urgent demand.

Following up: using math to model water equity

Gandolfo-Lucia’s work informed a subsequent Sustainability Scholars project by Thais Ayres Rebello to create an objective index using location and population indicators to calculate the number of water fountains necessary to achieve equitable water access in the City of Vancouver. Rebello worked to improve drinking water access in the city through the creation of a mathematical model, which led them to identify the need to install over 300 new drinking water fountains.

Read the follow-up report ‘An Objective Index for Equitable Water Access: A Public Drinking Water Fountain calculation for the City of Vancouver.’

The project ‘Accessible and Equitable Drinking Fountain Placement Strategy’ was completed by Nick Gandolfo-Lucia, a 2022 participant in the Sustainability Scholars Program, managed by the UBC Sustainability Hub.

Learn more about the Sustainability Scholars program.